They’ve got a good head on their shoulders.

In society, this is synonymous with being a reasonable, thoughtful person who makes good choices. This good head is what helps make ethical decisions, decisions one puts effort toward to be of value to society.

But how do our shoulders metaphorically play a role? Unlike the one head, there are two shoulders, on opposite sides of each other. Perhaps they represent the options we have, which sometimes present a conflict to our head that swivels back and forth as it takes in different information and considers context. When we make decisions that are inhumane, devilish, and foolish, have our shoulders convinced us that those decisions are morally right when they are ethically wrong, or vice versa? Do we think we are following our conscience when we are being persuaded by the devil on one shoulder and the angel on the other, just like in an animated children’s movie?

Or, referencing another idiom, do our shoulders have too many chips on them? I think that our various identifiers serve as chips on our shoulders. Our race, religion, sexuality, and more all predispose us to specific biases that can lead to unethical decisions. Following your conscience requires you to remove those chips, those hunches, grudges and egocentric traits that come along with the privileges we do or do not have. The skewed viewpoints that have been instilled in me while growing up in a sheltered, privileged town are the chips I am attempting to knock off my shoulders.

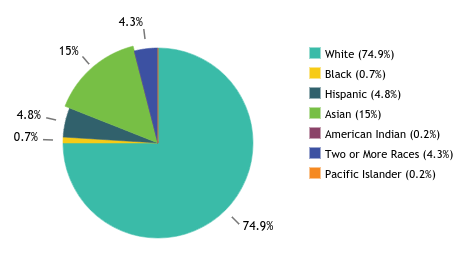

A visual representation of the racial demographics of my high school, Glenbrook North. Although numbers can never tell the whole story, this chart demonstrates how little diversity I experience at my school. I acknowledge how this oblivion, even on the surface level, serves as a chip on my shoulder that I need to remove by exposing myself to more of the world. Source: Illinois Report Card

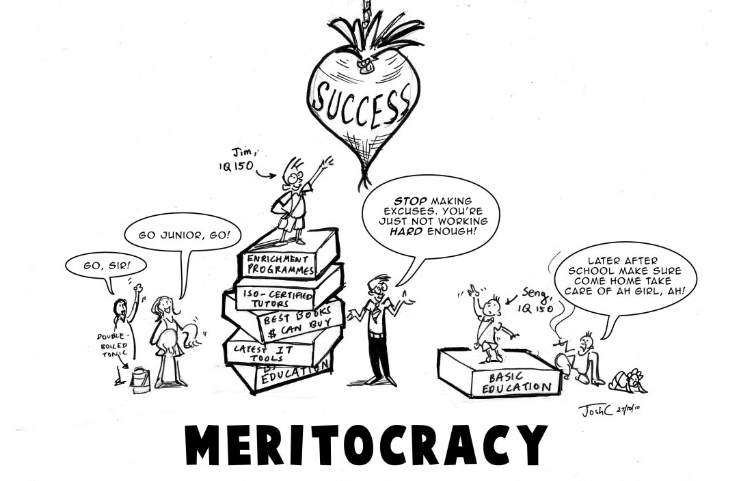

Peggy McIntosh explains in “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” how the advantages we were born with and those that accompany our social identity profiles not only lead us to have unfair biases, but also tempt us to stay locked in the sheltered bubble of a dominant lifestyle. She writes, “The pressure to avoid it [addressing our privileges] is great, for in facing it I must give up the myth of meritocracy” (5). Meritocracy is the governing of a society in which every individual has the ability to be recognized for their achievements, an idealistic world where inborn privilege is a foreign concept and hard work leads to deserved success.

A cartoon on meritocracy by Josh C. Lyman that illustrates the destructive power of privilege in terms of achieving equality. By using my conscience, I am able to admit that the environment I was raised in reflects the left side, and that same environment has taught me to subconsciously look down on those exemplified on the right side of the cartoon, in the same way the man is. This is a chip on my shoulder I am working on breaking down, as I aim to help lessen the divide between the privileged and the poor. Source: Anthea Indira Ong on Medium.com

It’s discouraging that we have molded a society where some are born into luxury and others are born into hopelessness, even though we all supposedly enter life with the potential to exercise strong shoulders in building good heads. This is our doing; we have created these social divisions, these institutions that cause greater divisions, these stereotypes and biases that cloud our vision, and the actions that limit freedoms of others. It is time to use our sense of conscience, what we perceive as right or wrong in our own conduct, in order to change the setbacks of our society that make the world an unsettling place.

Introspection is necessary to tackle this overwhelming task. We must work to reverse a notion explained in Arthur Miller’s adaptation of the play Enemy of the People, when Mrs.Stockman says, “There’s so much injustice in the world! You’ve simply got to learn to live with it” (35) when the citizens are struggling with deciding if health or wealth is more important. Having this ignorant attitude is taking the easy way out, while learning to use our conscience is challenging but necessary to start forging a good head on our shoulders.

Costume designs for “Enemy of the People” for the Goodman Theater in Chicago by Ana Kuzmanic. To me, these costumes represent how authoritative power of a government head has the ability to alter an entire town’s sense of conscience. People are left in the dark while making a difficult decision of whether health or wealth are of more value, and many chose to live with the injustice instead of facing the facts. Photo Courtesy of The New York Times.

Wheatley also write books about leadership; Who Do We Choose To Be? specifically highlights how all humans have the potential to follow our conscience as long as we put in effort to exercise these “shoulders”. She specifically writes, “I know it is possible to create islands of sanity in the midst of wildly disruptive seas” (9). Source: Google Books

Margaret J. Wheatley serves as a strong role model as she explains in her article “Willing to Be Disturbed” her own thought process when using her conscience. She writes, “When I hear myself saying, ‘How could anyone believe something like that?’ a bright light comes on for me to see my own beliefs. These moments are great gifts. If I can see my beliefs and assumptions, I can decide whether I still value them” (3). A moment of revelation, whether it instantaneously develops or grows over an extended time period, is truly a gift, yet it takes deliberate effort to see a challenge to our character as an opportunity for positive change.

Psychology discusses how it is human nature to protect our sense of self-concept, our beliefs we hold about ourselves and how we impact others. Paul and Elder explain this idea in their handbook, “The Thinker’s Guide to Ethical Reasoning”, writing, “There are too many ways in which humans can rationalize their rapacious desires and feel justified in taking advantage of those weaker or less able to protect themselves” (Paul and Elder 23). Using our conscience breaks down the walls we build around ourselves that don’t expose us to the reality of our decisions, telling us it’s time to face the facts.

Using our conscience can also fortify our decisions, even in the face of judgment by others. Reflecting on my own experiences, I can identify times when I have succumbed to a devil on my shoulder and times when I have followed my moral compass. An example that clearly stands out is my decision to not eat meat. After doing thorough research on the effects of eating meat on personal health and the environment and on the inhumane processes in the industry, I made the choice to give up animal products. Although I knew this new social identity could elicit negative feedback and backhanded jokes, I stayed confident in my ability to make ethical decisions based off of the good head I built on my educated but emotive shoulders.

Exercising conscience, which uses our moral compass based on ethical reasoning, helps us look ourselves in the mirror and feel confident in the actions we take. Let’s use this mirror to see where our shoulders fall short, and then let’s strengthen them.