The definition of rent as we all know it: “A tenant’s regular payment to a landlord for the use of property or land,” according to the Oxford dictionary.

The far less common definition of rent (also described in the Oxford dictionary): “A large tear”. A large tear, a rip in the fabric, a hole in the roof, a puncture of a noun, any place, thing, or person. “Rent” is no longer solely about the responsibility to pay for the roof over one’s head, but also about experiencing the harsh realities life can wield.

And that’s exactly what Jonathan Larson successfully aims to do in his award-winning Broadway musical, Rent. The characters are forced to learn how to shield themselves from, or choose to embrace, all of the adversity thrown at them: poverty, AIDS, drug abuse, complex relationships, etc. Set in the New York City ‘90s, the main characters struggle with paying their rent, while simultaneously mending their personal rents.

My mom and I outside of the theater where the production was held. Photo courtesy of me.

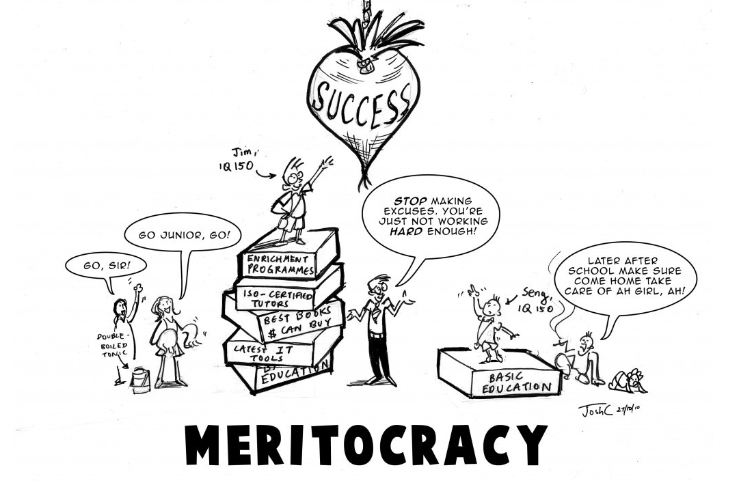

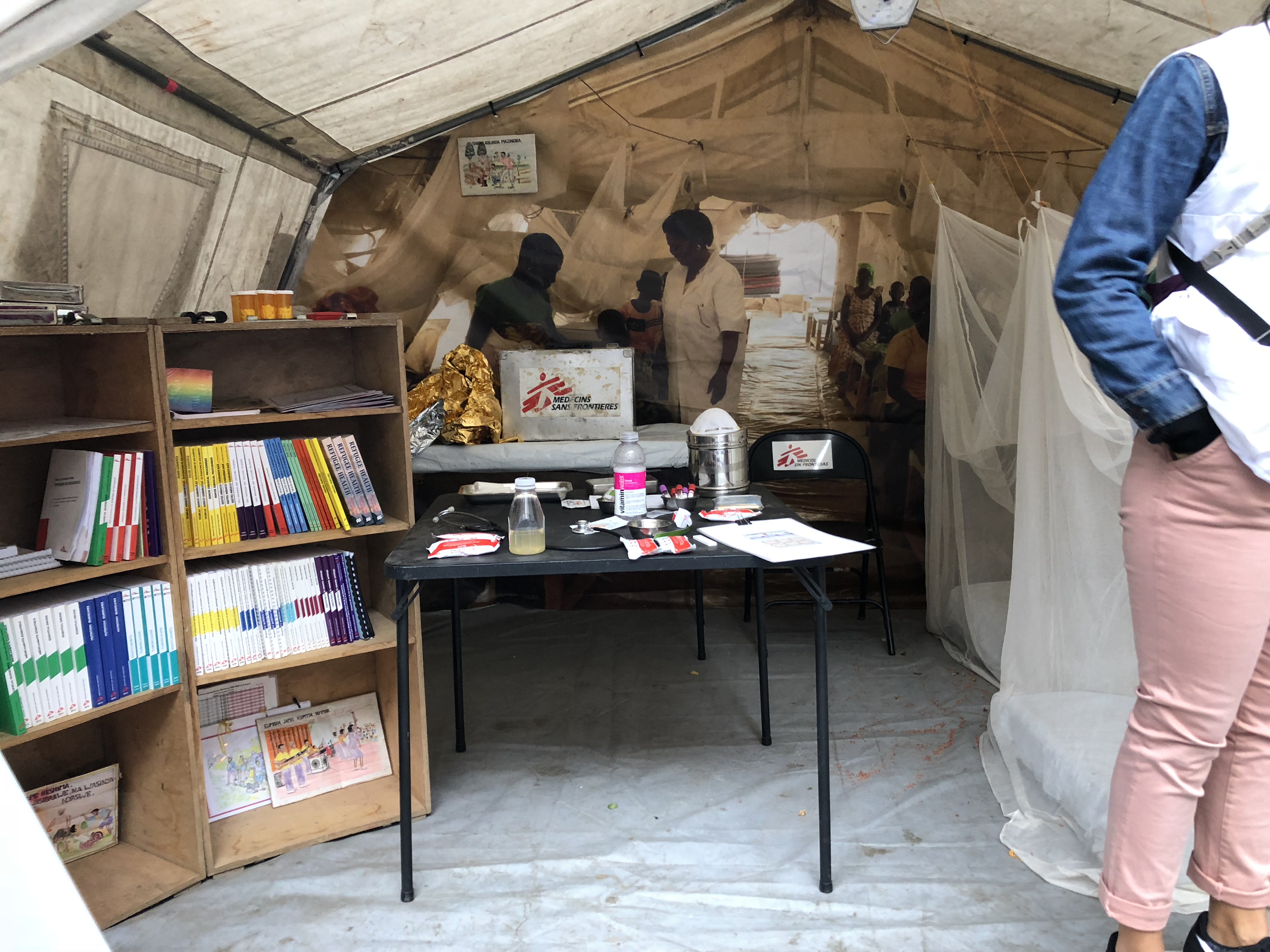

Although a wide array of crucial social issues are addressed throughout the intricate storyline, the most outstanding affair was the combination of having AIDS and no money to handle it. In true SAMO fashion, the AIDS epidemic was completely out of my previous realm of attention, as I had never been educated on the topic even though it is still a very prevalent social issue.

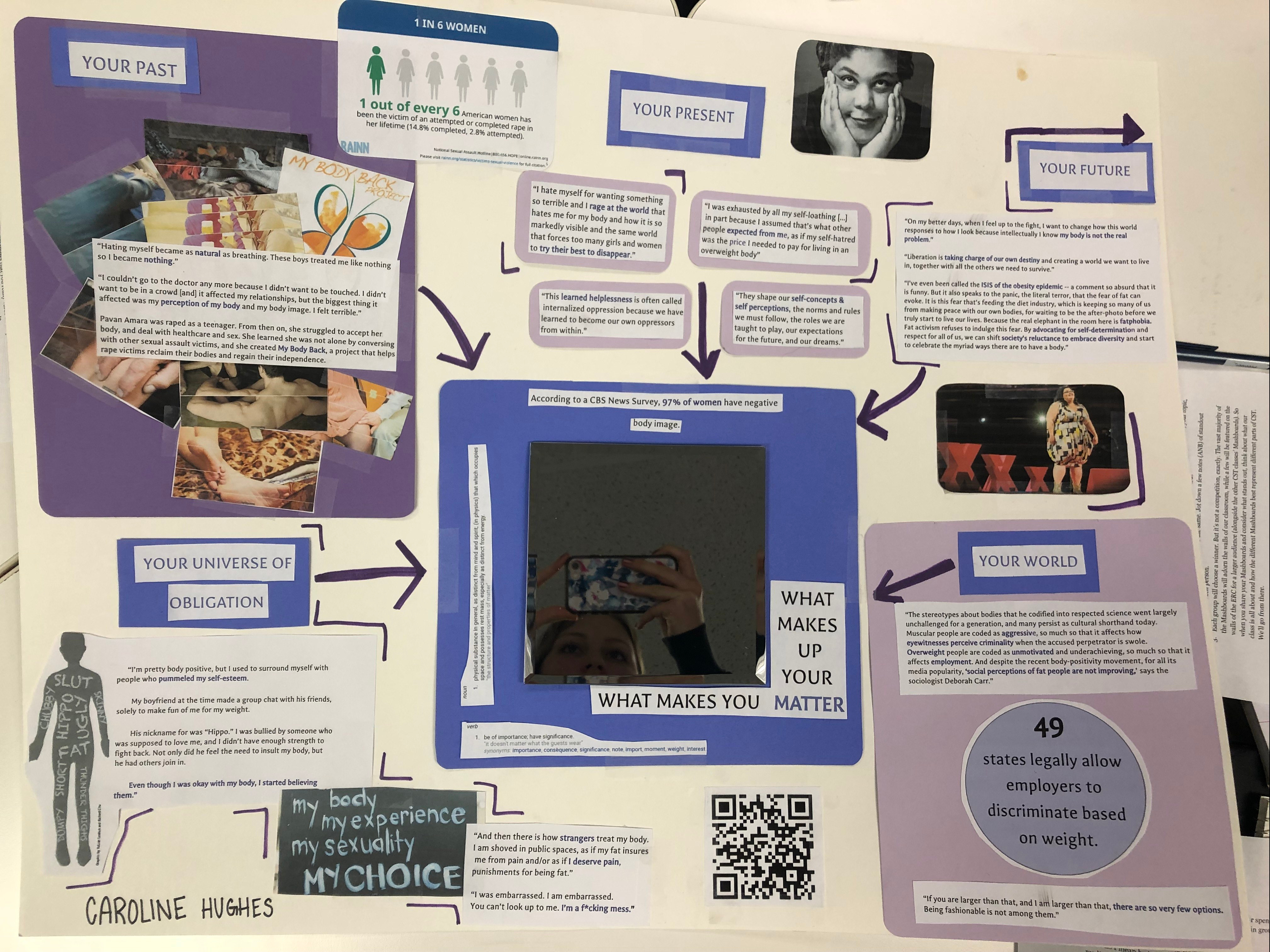

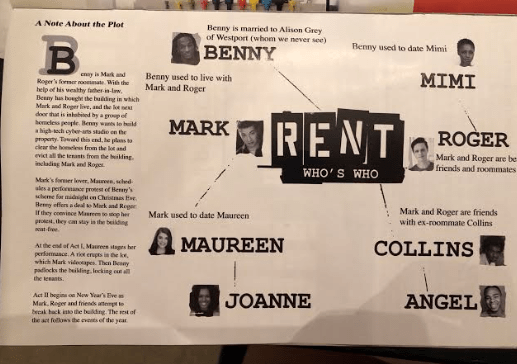

For a brief background on the storyline of the show, please refer to the image below:

Source: Rent Playbill

Roger and Mimi represent two of the main characters who struggle with being HIV positive. The two, as well as Roger’s ex-girlfriend April, demonstrate different ways that an HIV positive person may deal with this “rent”. April committed suicide (before the show begins) right when she receives the news of her diagnosis, hopeless about her future. Roger then deals with this mourning of April as well as his own intense fear of dying by rarely leaving his house, and obsessing about the one good song he must write before he dies. Finally, Mimi, who is only 19, lands on the other side of the spectrum, as she claims there is no time to live besides in the present. In one of her classic songs, “Another Day”, she sings: There’s only yes, Only tonight, We must let go, To know what’s right, No other course, No other way, No day but today”. All three coping mechanisms center around the toxicity of HIV and AIDS, as death is rarely a question. Add this dark cloud to their already impoverished lives, and it becomes clear why Rent is a musical rooted in social issues.

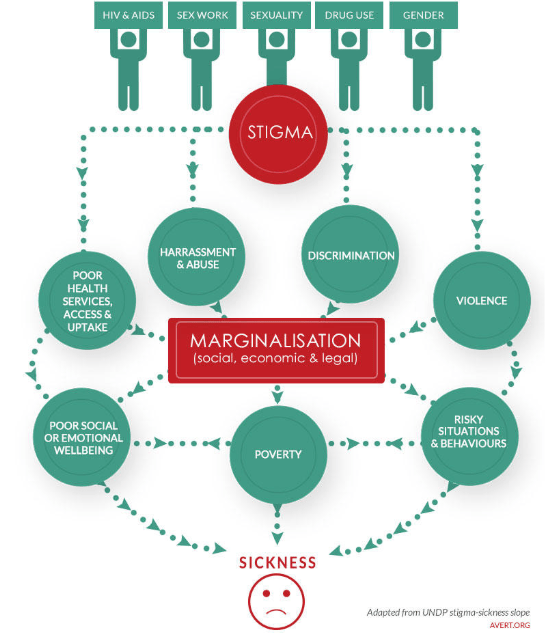

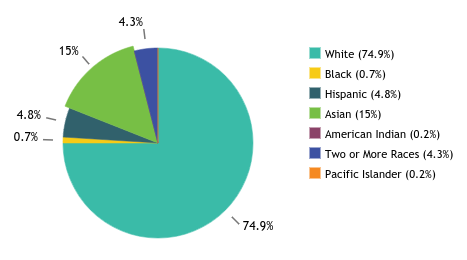

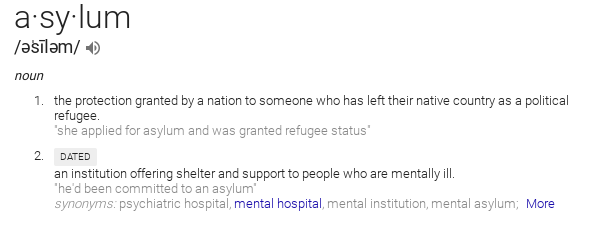

All of the characters in the show are constantly struggling with introducing themselves to, and creating relationships with, new people, as they must eventually reveal that they carry the “baggage” of the disease. This neglect of speaking candidly about their condition roots in the fear of discrimination and stigma that molds around HIV and AIDS. Avert, a UK-based charity, fights for the reduction of this stigma and to grow a greater awareness of the truth of this disease. In Avert’s article titled, “HIV Stigma and Discrimination,” the charity highlights the main causes of this stigma: the association with death, the belief that it is only transmitted through sex, moral fault or irresponsibility, etc. Although all could be considered valid, the cause of stigma that most closely aligns with CST ideas is the false belief that “HIV is associated with behaviours that some people disapprove of (such as homosexuality, drug use, sex work or infidelity)” (Avert). Because of this, people who are already part of target groups that Bobbie Harro describe in “The cycle of socialization” get loaded with more target social identities. For example, a black homosexual man may already face discrimination for his natural qualities, but if he were to be unfortunately diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, he would only be further isolated to the outskirts of society.

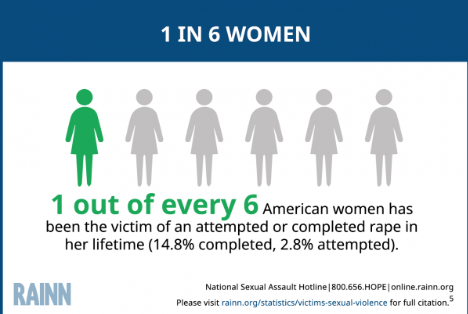

Avert specifically highlights this marginalization through their infographic that explains how discrimination can lead to poverty and poverty can lead to a lack of healthcare resources.

Harro’s piece specifically parallels this self-fulfilling prophecy as she writes, “This learned helplessness is often called internalized oppression because we learned to become our own oppressors from within” (5). If people with HIV/AIDS are consistently told they are not good enough to hold a job or find love and build a family, their own self-esteem level and motivation plummets, causing them to be prone to a desperate lifestyle.

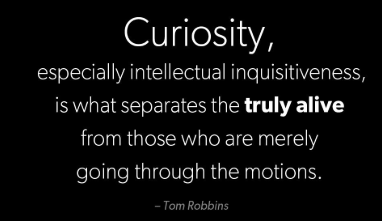

Avert additionally notes that the stigma actually causes the further development of the virus, as it has the power to delay one from getting the treatment they need due to shame: “UNAIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO) cites fear of stigma and discrimination as the main reason why people are reluctant to get tested, disclose their HIV status and take antiretroviral drugs (ARVs)”. Let that sink in: stubborn, ignorant biases about an extremely life-threatening disease are a cause of fatality. If that information does not serve as motivation to educate yourself and your community about the realities of this condition, I’m not quite sure what could be. As with most social issues, education on real-world issues (such as those discussed in CST) is the key toward achieving a more empathetic world. Margaret J. Wheatley highlights this in her article, “Willing to be Disturbed” when she writes, “It’s not our differences that divide us. It’s our judgments about each other that do. Curiosity and good listening bring us back together” (4). Judgments create rumors, rumors create societal beliefs, and societal beliefs create stigma and discrimination. The cycle repeats until the true or untrue belief becomes a well-known fact without validity.

In the case of HIV/AIDS, this “well-known fact” took on the form of laws. Avert reports, “Criminalisation of key affected populations remains widespread with 60% of countries reporting laws, regulations or policies that present obstacles to providing effective HIV prevention, treatment, care and support. As of 2016, 73 countries criminalized same sex activity”. This stigma developed into laws that prohibit patients, and their perceived target groups, from recieving the the treatment that should be a civil right.

Saving innocent human lives somehow got lost in the mix of politics. It’s time to get our priorities in line.

The Rent Playbill. Photo courtesy of me.

The characters in Rent were all able to find joy in their lives without materialism or good health through friendship and perseverance. In his poem, “The Person Sitting Next to You,” Ross Snyder writes, “She also has the right to be understood. And unless she can be understood by other people, she is thwarted from being a person” (1). Despite being “thwarted” by society, Roger, Mimi and those in their community understood and empathized with one another, giving them a bond centered around humanity.

Humanity gets lost in politics, formulating stigmas that kill. Words truly are a weapon, so it’s time to start choosing those words, as Larson did so cleverly with the musical’s title, wisely.

My mom and I enjoying the walk to the theater in the sunshine 🙂 Photo courtesy of me.